Adele, the British singing sensation with the two-octave range and the string of chart-topping ballads, has spent most of the past three years lulling her young son to sleep with nursery rhymes. “When I’m singing a nursery rhyme I just sound like everyone else,” she laughs. “You can’t really sing a nursery rhyme that well.”

The big-voiced songstress is back in the charts with her latest album, 25. It’s the first since the phenomenally successful 21, and the first since she gave birth to her son Angelo, now aged three. It’s about growing up, clearing out old regrets and getting comfortable in one’s own skin. It’s about “where I’m at right now”.

“I think my voice is better on this album,” says the 27-year-old Londoner. “The albums are named after my age and I like myself much better as I get older. I love 21 and I’m very proud of it but when I listen back to it, I’m very 21. You know, my outlook on everything and my thought processes. I don’t, like, word-vomit any more.” She cackles then adds, “Or at least I try not to.”

It’s almost eight years since Adele Adkins burst onto the scene with her debut album 19, in January 2008. Critics quickly dubbed her the best of her generation, as good as Joni Mitchell and Aretha Franklin.

Three years later, in January 2011, her second album, 21, debuted at No. 1 on the UK charts. It went on to win seven Grammy Awards and sell more than 30 million copies worldwide.

I speak to Adele a few days before the new album drops, in her only Australian interview. She’s sitting in her car, on her way to a voice-coaching session, wearing her “ordinary Londoner” camouflage: beanie, sweat pants and a big overcoat. “I’m sure I could get away with it,” she says. “I get away with it a lot.”

She is notoriously savage in protecting her privacy. Last year, she and her partner, charity entrepreneur Simon Konecki, successfully sued a British photo agency for taking pictures of baby Angelo at the park. She continues to take Angelo to the park, sometimes taunting the paparazzi but for the most part flying beneath the radar.

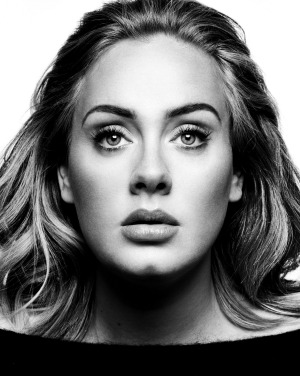

“It helps that I have a complete look when I’m on stage,” she says. “The hair, the eyelashes, the dresses, the jewellery – I love it, but I couldn’t make myself look like that every day, even if I tried. I wear 10 pairs of eyelashes, I contour myself to death – I don’t look like how I look normally in real life.”

“The hair, the eyelashes, the dresses, the jewellery – I love it, but I couldn’t make myself look like that every day, even if I tried.”

Adele has perfected the art of the celebrity interview, too. She’s friendly and polite, yet guarded and taut, as though at any moment she could snap and call the whole thing off. What she wants, she admits, is fame’s holy grail – to make art and live a normal life.

“If I just lived in the limelight constantly that’s not a very relatable life,” she says. “What do you write about? Do you write about other people’s thoughts? They don’t know what it’s like to be famous, what it’s like to be privileged.”

There was a time when Adele could walk into a studio and belt out her honeyed soul almost on command.

A vocal haemorrhage in 2011 made her cautious. Microsurgery to her vocal cords gave her four extra notes at the top of her range but it also forced the cancellation of the US tour to promote 21. These days, in addition to warming up and warming down, she keeps a strict(ish) diet. No caffeine, no alcohol. Nothing spicy, citrusy, tangy or sharp. Since Angelo, the cigarettes have gone, too, and she’s swapped long boozy lunches with friends for tall smoothies and gym sessions. Though she admits the sugar, which she also ditched, has since crept back in.

“It’s f—ing boring,” she shrieks. “But I don’t think you take [your voice] seriously until you’ve had an incident. I’m frightened all the time I’m going to damage my voice. A friend said I was like a surfer who’s been bitten by a shark and is too scared to get back into the water. I haven’t been singing for a reason other than absolute pleasure for four years. And now the pressure is on for me to be on form and I’m making an issue out of nothing in my head.”

About a year and a half ago, Adele thought she had enough material for an album. She showed it to producer Rick Rubin, who was instrumental in the success of 21. He listened and said: “I don’t believe you.” Adele took a deep breath and started over.

“I took it on the chin,” she says. “I kind of agreed with him. I deep down knew it anyway.”

That first collection of demos had six songs all about her son. But the dreamy-fierce love that comes with being a new mother didn’t translate. “It wasn’t obvious what I was talking about, so you just listened and you didn’t feel anything,” she says.

Adele regrouped. She listened to Madonna’s Ray of Light – the first album the Material Girl released after her daughter Lourdes was born. She felt she had to rediscover her artistic self.

“I had to decide what I wanted to write about,” she tells me. “So I sifted through my past, which ended up becoming the main theme of the record in the end. Once I found that, I found the songs came a lot better. And after that I felt I didn’t need anyone else’s opinion because I finally had my own on my music.”

“I had to decide what I wanted to write about.”

Yet because fame has come so fast there’s a lurking fear that she hasn’t earned it. An imposter syndrome not even a net worth of $US75 million can put to rest.

“I seem to get more intense the more that things take off,” she says. “I don’t think I’m insecure in terms of my music. [But] I feel it’s so unlikely that anything like this would ever happen to someone like me. It’s still pretty out there, really. Still pretty hard to digest.”

She recently told Rolling Stone: “I always feel like this is going to turn out to be a hidden-camera show, and someone is going to send me back to Tottenham”.

In Tottenham, she was born to an 18-year-old mother. Her father left when she was three, and she and her mother moved frequently, from flat to tiny flat. These days, her property portfolio includes two London homes worth more than £10 million. Angelo, almost certainly, will have a completely different life.

“I think about that every day,” she says. “But my partner, his dad, Simon, isn’t famous, so I think that balances us out really well. I’m not very comfortable being famous. I’m still the same as I was all those years ago. I live a different life, but it’s not as spectacular as it probably could be if I got carried away with myself.” (She pronounces the last two words as “wiv meself”, revealing endearing traces of an earthy Cockney accent.)

Folksy legends about Adele abound. She went to 10 schools. She cancelled part of her first US tour, to spend more time with the tour photographer, Alex Sturrock – the (ultimately) ex-lover who became fresh lyric-fodder for 21. And in her first press interviews in Britain, she proudly named the Spice Girls as her biggest influence.

Along the way, she has gained some smarts. She describes her manager since 2006, Jonathan Dickins, as “the best part of everything”. And for 25, she collaborated with some of the finest in the business – in particular Max Martin, the Swede who’s also worked with Britney Spears, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry and Pink. “I tend to pick people based on the work they’ve done that I really like. I’m still more of a fan than an artist, I think.”

Her own brilliant career she puts down to good fortune. “I think its just luck,” she says. “And the stars aligning, and good timing.”

As yet, there are no plans to tour the album: “I’m scared of flying,” she admits. But any tour will certainly include Australia, where her new single, Hello, debuted at No. 1 on the Aria charts, with platinum sales in its first two weeks.

“I think it’s just luck, and the stars aligning, and good timing.”

It’s a conundrum, this thing called fame. Why does one singer succeed while another, equally good, never makes it? Adele, too, is stumped for an answer.

“Honestly I dunno,” she says. “I’ve got no idea. If I did, I’d sell the formula. I’ve got so many rough edges – with the way I look, with the way I talk – even with the way I sing, you know. I can give a dodgy performance sometimes, like I haven’t mastered my craft, and I think that’s why people like it. Because it’s rough around the edges.”

This story originally appeared in The Sun-Herald’s Sunday Life magazine on 22 November 2015.

Photo: XL